WRITTEN WORK

January 8, 2025

Another Job of Sumo Referees: Writing Rankings by Hand

In this series, Kaku Shigoto (Writing for Work), we look at a variety of jobs that create something through writing or drawing. In this third installment, we shine a spotlight on the banzuke (official rankings) that are crucial to sumo tournaments, and introduce the work of the sumo referees who write them.

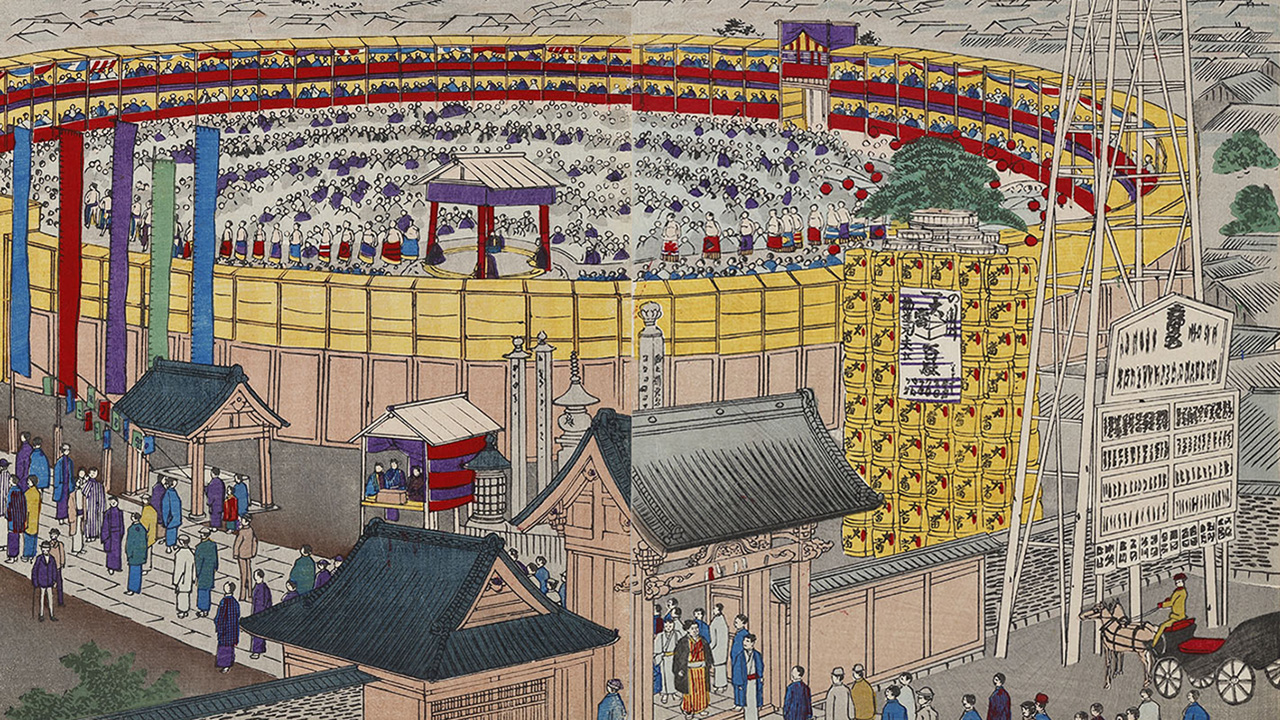

We often hear the word “ranking” (or banzuke in Japanese) as it relates to hot products and the best hot springs in Japan. The origin of the word banzuke comes from sumo, Japan’s national sport. In sumo, the banzuke lists not only wrestlers but also elders and referees in order of seniority for each official tournament held six times a year. It is essentially the ranking table of the sumo world. Did you know that even today, it is the job of sumo referees to write these rankings by hand?

When you think of a sumo referee, you probably think of someone who makes the call on which wrestler wins in the sumo ring. But their job is not limited to the sumo ring. They are also in charge of announcing the winners and prizes within the arena, and play an important role through writing in a variety of necessary settings behind the scenes, including the banzuke rankings.

In this installment, we spoke with Kimura Yonosuke II, a Makuuchi division referee who is the 8th person since World War II to take on the role of writing the banzuke.

For more information on the history of banzuke (External link: NIHON SUMO KYOKAI) 〉〉〉

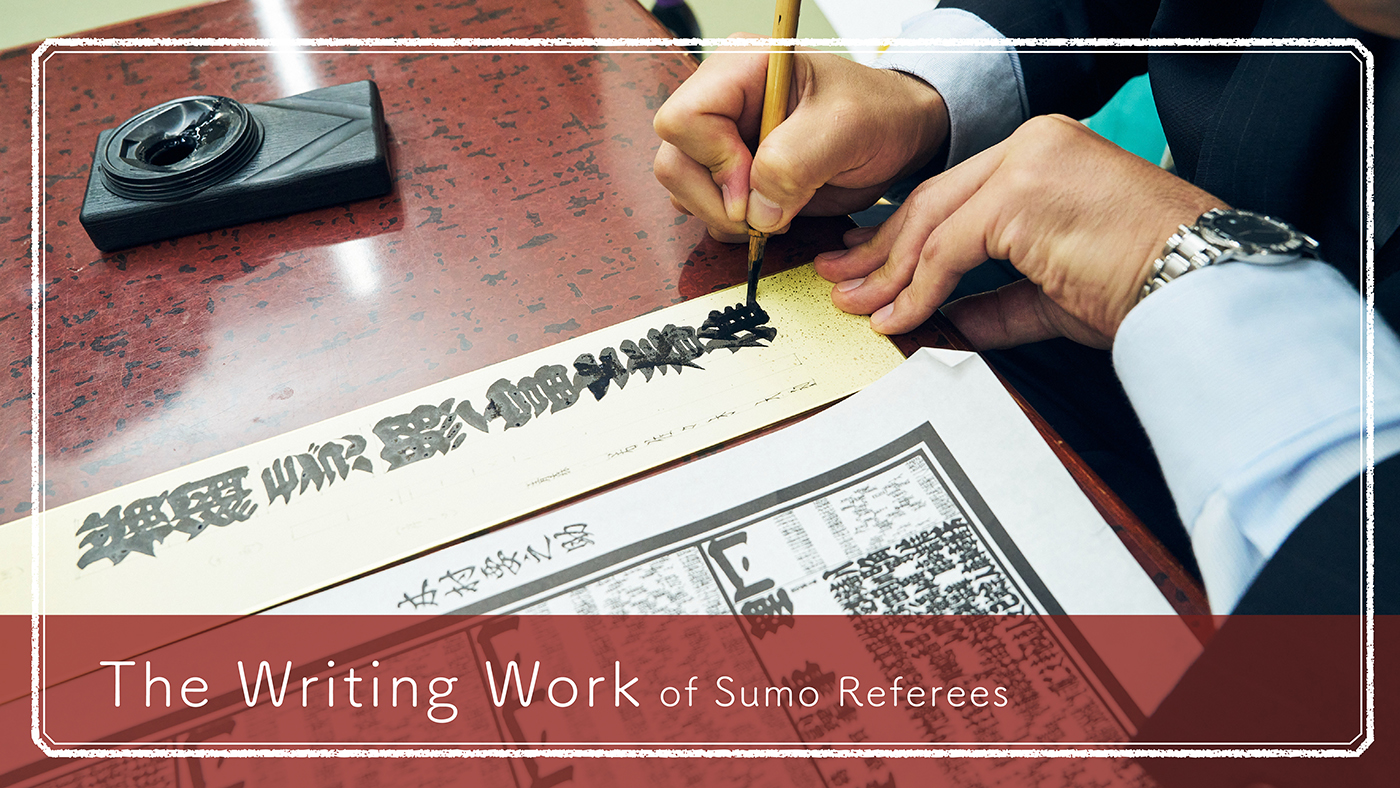

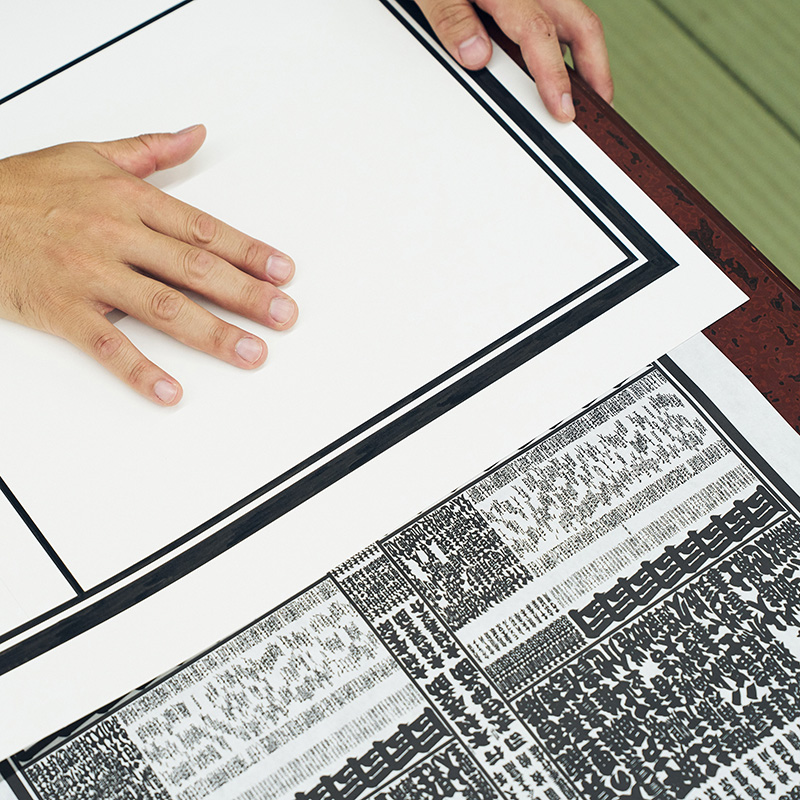

In the dressing room at the Ryogoku Kokugikan Sumo Arena, Yonosuke showed us a dozen or so referees with brushes in their hands, writing on desks and banzuke boards.

“You might be surprised, but referees have quite a lot of work involving writing. Of course, they create the original version of the paper banzuke that is announced and distributed before each tournament, but their work goes far beyond that. Even just focusing on tasks related to the banzuke, there is the large banzuke board that stands near the entrance to the arena, the illuminated scoreboard displaying wrestler names on the east and west sides inside the arena, the maki, a scroll of washi paper that records the results of each bout, and the draft of the win-loss table that is published after each tournament. In all, there is quite a lot we have to write.”

In some rooms, referees also handwrite invitations for ceremonies and promotions, as well as address envelopes. The writing work of a referee is essential not only during tournaments but also for the overall operation of professional sumo.

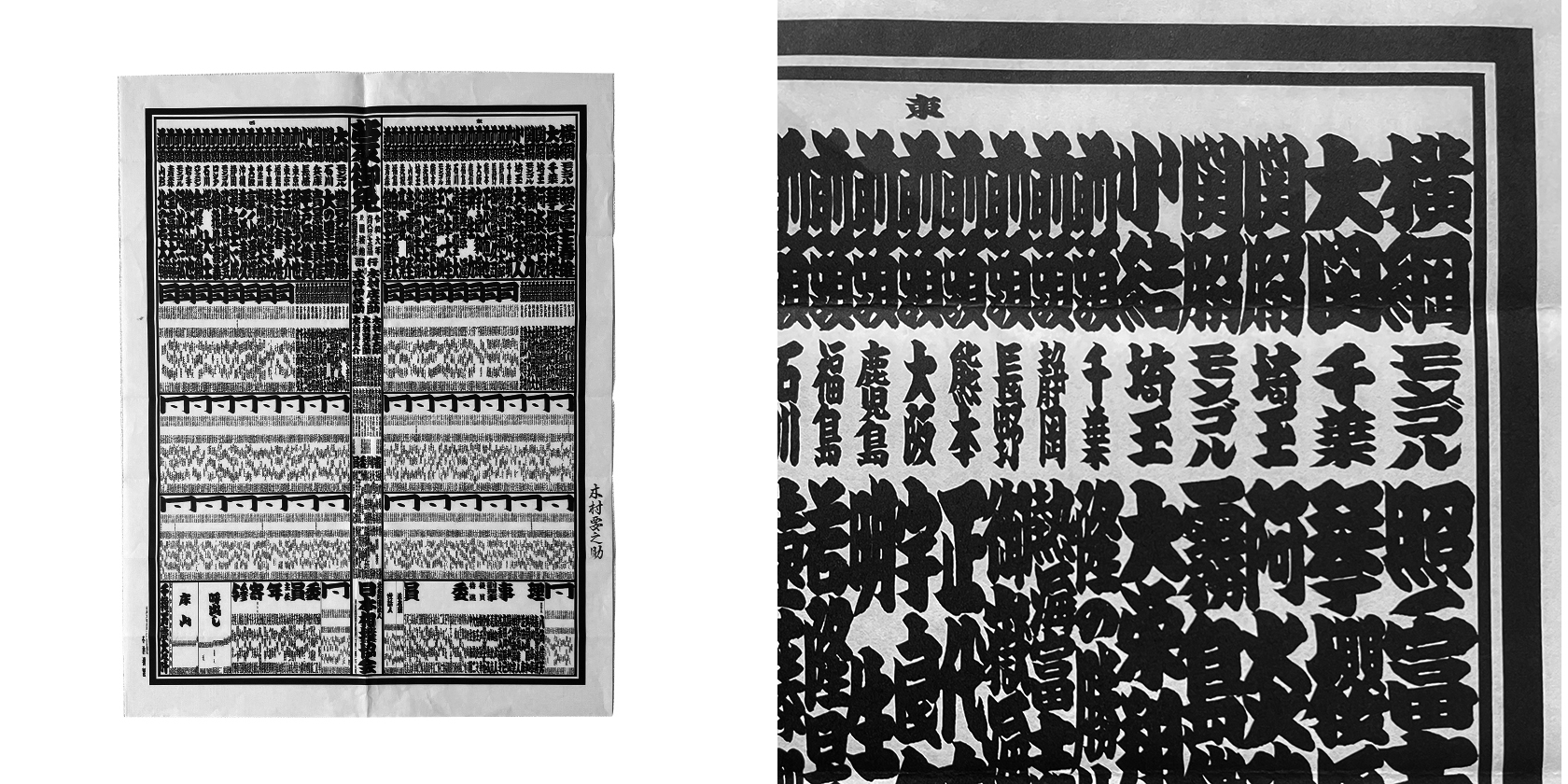

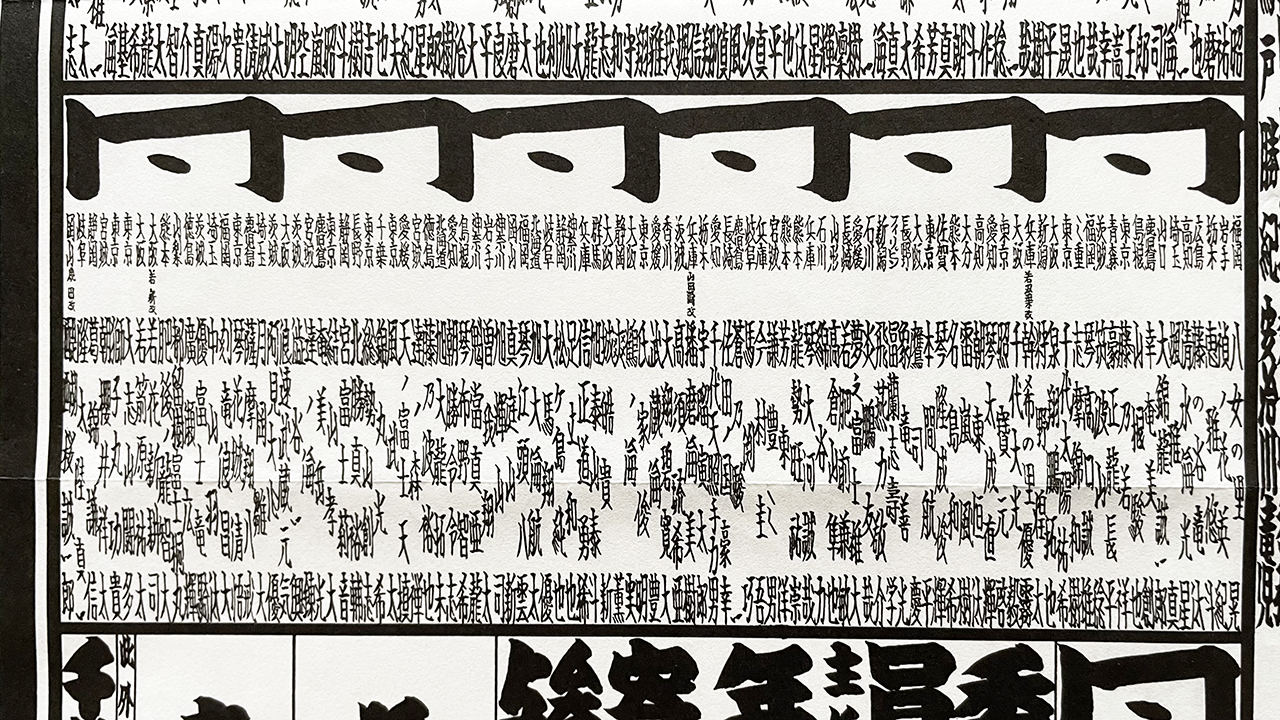

Today, the first thing that is announced and distributed before a tournament is the paper banzuke. While the distributed version is about A2 size, the original draft is written on pure white Kent paper about four times as large, measuring 110 by 80 cm. The left and right sides of the paper represent east and west, with five columns each. From the first to fifth columns, the names of roughly 600 wrestlers are written in rank order: Yokozuna, Ozeki, Sekiwake, Komusubi, Maegashira, Juryo, Makushita, Sandanme, Jonidan, and Jonokuchi. This is followed by the names of the directors, committee members, attendants, trainers of young wrestlers, elders, ushers, and hairdressers. In the center are inscribed the names of the referees along with the Nihon Sumo Kyokai.

The work of a referee in writing the banzuke begins the day after the close of the previous tournament. They have to create the new banzuke for the next tournament.

“We gather up information on who is retiring and who has changed their name while also preparing to create the next banzuke in anticipation of the meeting to determine rankings held three days after the close of the previous tournament. Currently, together with my two assistants, the three of us are responsible for the banzuke. We do not participate in regional tours and instead dedicate ourselves to creating the banzuke. We attend the ranking meeting as secretaries, and the records from these meetings become the draft for the next banzuke.”

After the meeting, they carefully prepare a draft and review it, then draw frames by hand on the large Kent paper used for the original. The job of drawing these lines in ink falls to the assistants. This work alone takes a full day.

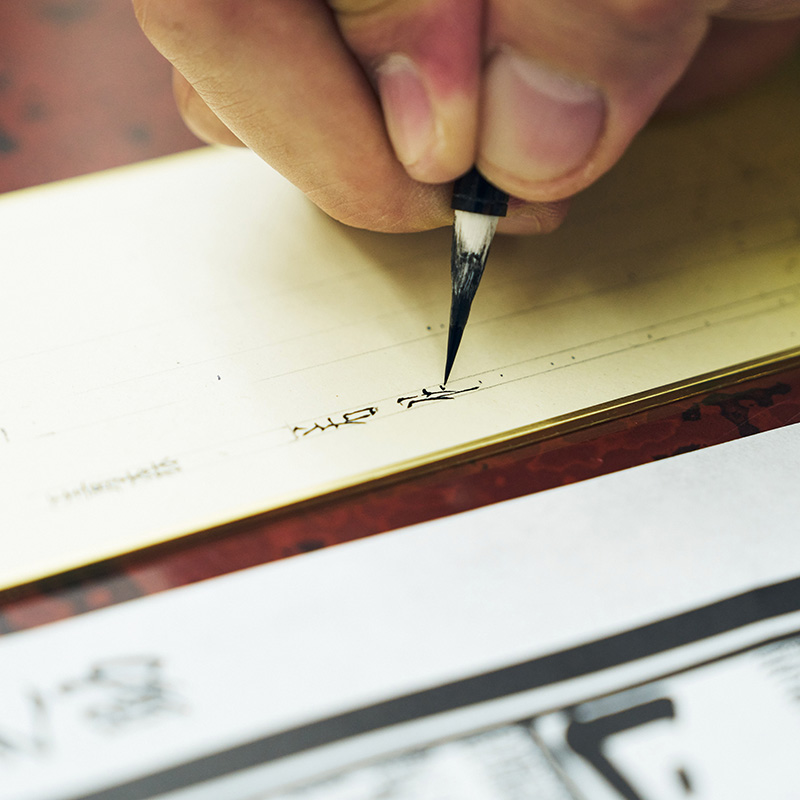

“Next, we calculate the width of each wrestler’s name for each row, and draw guide lines using a pencil. For example, if there are 98 names that need to be written in the fourth row on each side, we divide it into exactly 98 equal parts and draw the lines. The number of names per row differs each tournament, so precise calculations are required each time, making the process very time-consuming.”

Once it is time to actually write the names, Yonosuke cloisters himself in a room and carefully writes the names by hand, taking between 10 days to two weeks to complete. Once the draft is finished, the team of three checks for any mistakes, and from there, they hand it off to the printer, which produces about 600,000 copies of the banzuke at the reduced A2 size.

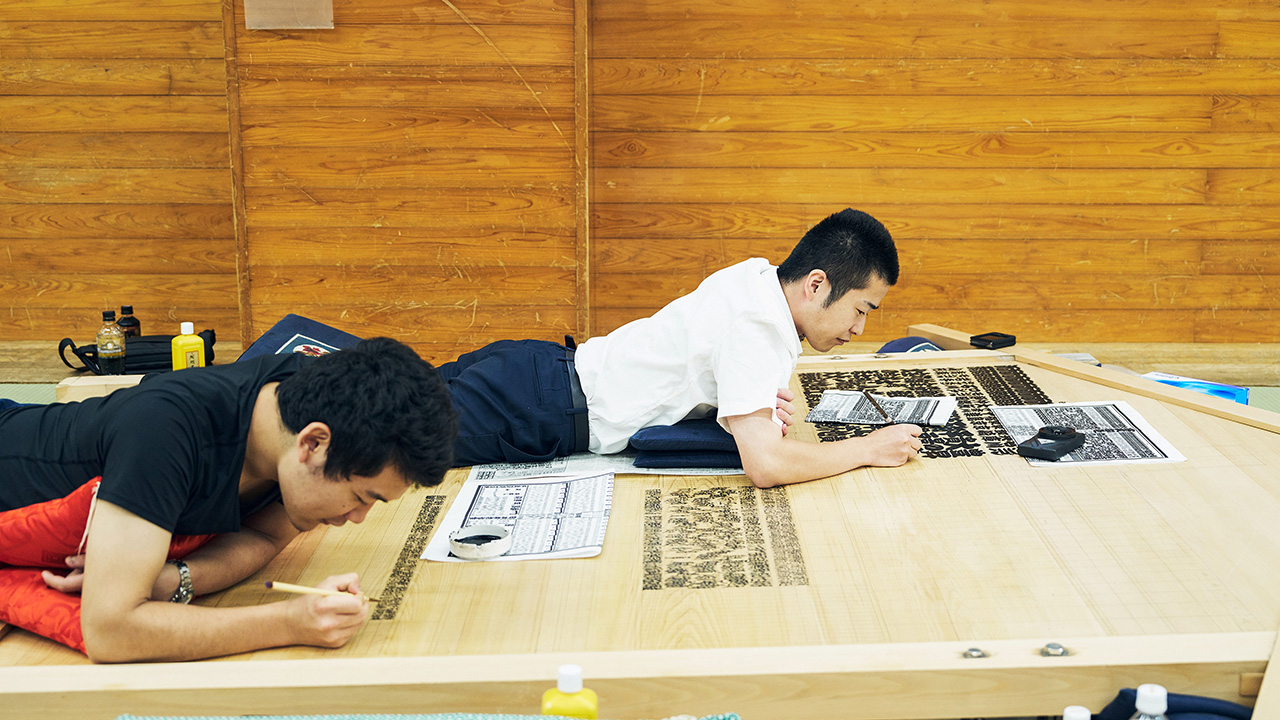

Another task for referees involving writing is the maki. This scroll records all of the results from the 15-day tournament.

The maki is made of connected sheets of Japanese washi paper, and just like the banzuke, the names of all wrestlers from Yokozuna down to Jonokuchi are written in ink. Space is left above and below each name to record wins and losses. The scroll, containing the names of around 600 wrestlers, stretches several meters in length, and a new one is written for each tournament.

During a tournament, the results of all 15 bouts for each wrestler (7 for those in the Makushita division and below) are recorded as follows: if a wrestler wins, the name of the opponent is stamped below their name, and if they lose, the opponent’s name is stamped above. One glance at the maki shows exactly how many wins and losses each wrestler has, making it an essential reference for determining opponents during the tournament as well as for deciding the rankings for the next tournament. This tradition has been passed down unchanged, and this analog method of record-keeping remains the same today. After the ranking meeting concludes, the maki is carefully stored in the Sumo Museum. It is occasionally put on display, but few people know of its existence.

“Before writing the first name, I write the word ‘mirror’ at the start of the maki. This signifies that the sumo wrestlers are being reflected on paper. This too is a tradition that has remained unchanged since olden times, and for those of us in the sumo world, we treat the maki as sacred objects, as important as human beings. It would be unthinkable to step over a maki. It is said that in the past, someone who stepped over one was severely reprimanded.”

The sight of these referees showing such reverence for the maki is a reminder that sumo is a sacred ritual.

For sumo referees, being able to write properly is as important a skill as being able to judge matches in the ring. When a referee joins the Sumo Kyokai, they are required to take courses in writing sumo calligraphy. The banzuke rankings are written using this unique sumo calligraphy, a unique brush style typeface used only in the world of sumo. The thick, tightly written characters are considered auspicious, symbolizing the hope that the sumo venue will be completely packed with no room to spare.

“When you become a referee, you have to be able to write sumo calligraphy or you can’t do the job. I wasn’t very good at writing myself, so I had no choice but to focus my efforts on practicing. There are even cases where people join only knowing the role of the referee in the ring and end up quitting. No matter how good you are at judging matches, you can’t perform the other duties of a referee without being able to write sumo calligraphy.”

Even if you don't possess skill in calligraphy, all referees must be able to properly do sumo calligraphy.

Yonosuke showed us the sample he used when he first entered training, explaining that the first characters taught in sumo calligraphy are “山川海” (mountain, river, and sea). Beginners practice writing these characters, which are often used in wrestlers’ ring names, gradually expanding their repertoire to include characters like “錦” (brocade) and “花” (flower).

“When I first entered training, I thought practicing the same characters over and over was boring,” Yonosuke said. “But the fewer strokes a character has, the harder it is to balance. Now that I’ve gained enough experience to serve as the calligrapher for the official banzuke, I can truly appreciate the depth of this art.”

Sumo calligraphy is unique in that the characters are especially thick, based on normal block-style characters. The final strokes on each character are written in a way that is different from normal Japanese calligraphy so as to fill in the space between characters. However, there are no fixed models or set forms for each character in sumo calligraphy, so writers are free to express individuality based on their own sense and feeling of balance. Yonosuke himself practiced by mimicking the calligraphy of other experienced referees and banzuke written by people in the past. He says that it takes writing countless characters and at least ten years of experience before you can arrange characters on your own. Even now, after more than 30 years of experience, Yonosuke says he is still not fully satisfied with his own ability.

The difficulty of sumo calligraphy also increases when a referee becomes responsible for the official banzuke. This is because when writing on Kent paper, which is about one-quarter the size of a wooden banzuke, the calligrapher must distinguish between the large, bold characters for Yokozuna and the thin characters for Jonokuchi. After learning the basics of sumo calligraphy characters, referees then move on to the maki, the wooden banzuke, and finally the official banzuke. As they gain experience in writing the various types of banzuke, they gradually have more opportunities to write smaller characters, moving from the large, bold characters to smaller ones.

“When I first started, I was taught to write fat characters that looked like sumo wrestlers. and when writing the wooden banzuke, I was told to make the characters so bold that the entire board looked almost black. Just as I was getting used to writing these thick, space-filling characters, I became an assistant for the official banzuke and had to start practicing writing small characters instead. Breaking the habit of writing thick characters and switching to thin ones is truly difficult. The draft paper for the official banzuke is much smaller than that used for the wooden version, so when writing names down to the lower ranks like Jonokuchi, the characters must be extremely small. Even though they are thinner, sumo calligraphy still has its distinctive features; It’s not ordinary block script, nor is it the same as thick sumo lettering. It’s very delicate work. Since becoming an assistant for the official banzuke, I’ve been practicing writing thinner characters, but I’m still not satisfied. Even now that I handle the drafts myself, I still feel I have room to grow. The only way to improve is to keep writing. It’s truly a lifelong pursuit,” he says, his expression conveying the difficult in mastering sumo calligraphy.

Referee teachers often emphasize two points: “Value the basics” and “Never try to show off.” For referees, mastering the basics is considered the most important aspect of their calligraphy skills. And when standing in the ring, the most important things are still the basics. Yonosuke himself did not fully understand what this meant when he was younger. But one day, when he saw his teacher continue to perform the basic movements even after attaining a higher rank, he came to understand the true depth of the basics.

“For example, you must raise the referee's fan at shoulder height, and no higher or lower. Of course, as you get older, it becomes harder to lift your shoulders. But if you’ve thoroughly mastered the basic form from a young age, even if the fan dips slightly, it still looks graceful. Even your family will say it looks good. The same applies both on in the ring and with sumo calligraphy.”

Even as he grows older, his commitment to the basics remains unchanged. There truly is a depth to the basics that can only be grasped through years of experience.

Yonosuke currently serves as a supervisor, one of three referees selected from those ranked in the Juryo division or higher. As a supervisor overseeing all referees, he holds a position of great responsibility, including instructing new trainees in sumo calligraphy and movements in the ring. Many people know about the sumo stable system, where a stablemaster lives and trains together with the wrestlers under one roof. But what about with referees? We asked Yonosuke.

“Just like wrestlers, referees belong to a sumo stable and generally live together with the stablemaster and wrestlers for about ten years after joining. The number of referees is capped at 45 (there are currently 43), and each belongs to a stable. While policies differ from stable to stable, referees learn their craft either from senior referees within their own stable or from seniors in the larger ichimon group made up of several stables. The influence of the senior members of the group is especially significant.”

That being said, all referees work together on writing tasks such as the maki and wooden banzuke. Unlike wrestlers, referees spend a great deal of time interacting and working with seniors and colleagues across different stables. There are many tasks done collaboratively, such as gluing together sheets of washi paper for the maki or writing on the wooden banzuke simultaneously with others. The same is true for the official banzuke that Yonosuke works on.

“After the ranking meeting, three of us handle everything from drafting to proofreading. I always tell my assistants that if they ever have a question or notice a mistake, they must speak up without hesitation. If I make an error and the assistant notices but doesn’t say anything, that mistake will end up printed on about 600,000 copies. It’s a huge responsibility. That’s why I encourage them to speak up whenever something feels off and make sure to create an environment where they can. The work of producing the official banzuke can never be done by one person alone. Being a referee is all about teamwork.”

The work of a sumo referee extends beyond the ring, with writing responsibilities being much more significant than you might imagine. While it may seem that digitizing certain aspects of this long-standing tradition would make things more efficient, it remains a tradition that has truly been preserved and passed down through the immense time and effort devoted to writing everything by hand.

“For each tournament, every handwritten method, rule, and procedure, including the banzuke, is entirely logical. Beneath what can be seen on the surface lies something profound yet unseen. That is because sumo is sacred.”

On the day before the tournament begins, the referee also serves as the officiant for the dohyo-matsuri, a purification ceremony for the ring held to pray for safety. His words left a lasting impression, evoking a deep sense of pride in carrying on a timeless cultural tradition to the next generation.

|

|

Special thanks to Makuuchi division referee Kimura Yonosuke. He was born in Ise, Mie Prefecture. He belongs to the Hakkaku stable. He debuted as Kimura Masashi in March 1990. In 1994, he took on the name Kimura Yonosuke, and in May 2015, he was promoted to the Makuuchi division. In March 2023, he took on the role of writing the banzuke. |

<

1

2

3

>